Thoughts on Communication and the Breath

In an earlier post I offered some thoughts on communication, specifically communication between ourselves and our bodies. That post emphasized how our muscles respond differently depending on what we’re telling them, and it highlighted the fact that we can solicit the response we want, muscularly, when we’re clear about our intentions and effective in communicating our message.

Now this topic is coming up again and I find myself talking about it frequently with my students. The difference is that I’m talking more about the ways our bodies seek to communicate with us, how we sometimes fail to listen and how this typically leads to a smaller, more manageable problem becoming a bigger one.

Yoga teachers will often speak of listening to our bodies for guidance. This is in part because a failure to listen to what our bodies are telling us inevitably leads to injury. I have asked my students to pay attention to what their bodies are trying to communicate. I have also mistakenly assumed that a student who is clearly not paying attention to their body’s message, or mine as the inststructor, is doing so intentionally.

I have made this extremely unfortuate and damaging mistake more than once and I aspire to never do it again. It’s the rare occasion when a student deliberately ignores their body’s message. The fact is, listening to our bodies for guidance is very difficult and actually following that guidance, should we hear it, even tougher. Therefore we need to be generous with ourselves as we practice and as teachers we need to be generous with our students and assume they are doing their best, even when they appear not to be listening.

We also need to remain vigilant when it comes to fostering this type of communication. In his final book, Light On Life, B.K.S. says:

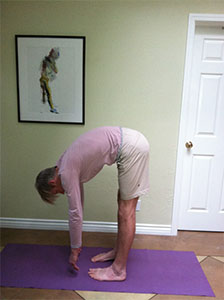

“Overstretching occurs when one loses contact with one’s center, with the divine core. Instead, the ego wants simply to stretch further, to reach the floor, regardless of its ability, rather that extending gradually from the center. Each movement must be an art. It is an art in which the Self is the only specatator. Keep your attention internal, not external, not worrying about what others see but what the Self sees.”

Iyengar’s statement reveals how the highest aspiration in yoga, to know the Self, is undermined by our most pedestrian of limitations, the ego. The ego,which we all have and must have to be well functioning human beings, runs interference between ourselves and the messages our body conveys. Iyenger illustrates here why the ego must be addressed if we’re to succeed in yoga.

I believe that most of my students aspire more to use yoga and/or movement to keep themselves out of pain and to function better and managing the ego may not be primary among their ambitions. My view is that these aspirations are not at odds with self knowledge but, on the contrary, are a necessary part of it. To resolve pain and improve movement we must be able to pay attention and hear the messages our body and mind are communicating to our intelligence, and this is also an essential skill for Self knowledge.

When two people are trying to communicate and they are having difficulty, often a moderator of some kind is helpful. Married couples might use a marriage counselor, for example, whose job it is to hear what a person is trying to say and then to convey that message to his or her spouse in a way that he/she will hear it. When we’re having difficulty communicating a message to our body, or hearing the message that our body is sending back, a moderator of a different sort can also be useful. The best moderator I’ve found in this instance is the breath.

When I use the word “breath” in teaching, as in the cue “use your breath,” I basically mean the mechanism by which the act of breathing relates to the body structurally and pschologically. When we inhale, for example, our diaphragm moves downward and increases pressure in the abdominal and pelvic cavities. This intra-abdominal pressure or IAP, as its known, is a powerul stablizing force that can be used to maintain functional alignment both in static postures and during motion. The IAP keeps our abdominal muscles and the pelvic floor working the right amount and at the appropriate times. The resulting trunk and pelvic stabilization facilitates greater mobility in our hips and shoulders and allows for freer movement.

These physical affects of IAP are also extremely reinforcing psychologically. When my IAP is working well, or said a different way, when my breath is working well, I feel stronger, more relaxed, more free in my movement and overall more at ease. In other words, when my breath is better I just plain feel better. Conversely, if my breath is not working well I don’t feel as good and it is likely an indication that my alignment is also not good.

This illustrates how my breath acts as a moderator to help me hear the messages my body sends and how it provides a powerful mechanism for responding to these messages when necessary. Even if I’m not quite sure what the source of my misalignment is, I can still make a correction by observing how the change affects my breath. And perhaps more importantly, even if I can’t improve my breath at that moment, at least I can use it to recognize that I need to come out of the posture or suspend my movement so that I don’t risk injury.

In Iyengar’s words, the breath can serve as “one’s center,” one’s “divine core,” and when he describes “extending gradually from the center” as opposed to an ego driven “overstretching” he alludes to how the breath can serve as the foundation for our postures and our momement. For this to happen we must recognize the difference between what “the ego wants” and what our body is telling us, and this requires that we “keep (y)our attention internal.” It requires that we remain in constant communication with the body and are not drawn away from its message by ego driven thoughts.

It is so important in yoga and movement that we don’t work at cross purposes. We need to keep asking ourselves the questions “why am I doing this” and “is this serving my primary interest.” If my answers are “to punish myself with exercise” and “yes but it’s not quite painful enough yet,” this is perfectly fine but then we need to recognize that my ego is the source of my motivation and not the needs of the body and mind I’m tasked with looking after. If we do recognize this and decide to move forward with the work anyway, at least we’re clear about why we’re doing it.

If on the other hand we see that the ego is driving the conversation then we have an opportunity to reevaluate our approach and seek other input. Our bodies are extremely good at giving feedback. Let’s strive to learn their language and hear their message.