Stair Mechanics – Walking Up

in Balance, Health Article, Movement Article, Personal Alignment Training, VideosIn this short video Tiffany details some of the most important features of functional mechanics when climbing stairs. This includes some of the most common mistakes and how to correct them.

High Lunge for Hip Stabilization and Mobilization

in Balance, Movement Article, Personal Alignment Training, Videos, YogaI’ve been really loving the short movement sequence shown in this video. It’s got a number of applications including stabilizing the hip joint, increasing range of motion in the hip, trunk stabilization and training for better throwing mechanics. I also find this sequence an ideal preparatory movement for classical standing asana in that it helps to awaken the movement patterns that really bring yogasana to life. Check it out!

Balance and Yoga

in Balance, YogaIn part one of the introduction to B.K.S. Iyengar’s classic book ‘Light On Yoga’ Iyengar spends 2 1/2 pages offering various definitions of yoga. One that I particularly like describes yoga as “…a poise of the soul which enables one to look at life in all it’s aspects evenly.” Considering this definition some other words come to mind which further suggest the meaning of yoga – “balance”, “control”, “calm”, “equanimity”, “grace”. Of these, I’d like to suggest that “balance” is the most fundamental component of any yoga practice.

The word “balance” can have very different meanings depending on how it’s used. For example, if “balance” is used as a verb it suggests something we do to acheive stability. . .poise. If I say to you, “balance on one leg!,” your mental and physical effort is directed into maintaining your position with one leg lifted. Standing on one leg can be challenging for many of us, but sometimes the effort to do it results in something very different from stabiltiy or poise. In fact, our effort to “balance” often results in an increase of tension in the body and mind that not only doesn’t help with balance but in fact impairs it. When we try to “do balancing” rather than recognizing and rectifying the cause of our instability our ability to balance remains elusive.

Recognizing and rectifying the cause of our instability requires that we train the mind not just to see what we need to do to acheive stability, but also to see what we are already doing that is promoting instability. As a human being with a mind I am very prone to habits. Perhaps I have a habit of standing with my hips pushed forward. I may do this so often that I don’t even see that I’m doing it until I have occasion to stand with my hips backed up over my ankles. Then my mind sees that I was pushing my hips forward and likely has been for some time. This recognition is the essential step to breaking the habit and changing what I do.

From the standpoint of balance, standing with my hips pushed forward is perhaps the most reliable thing I can do if I want to have difficulty balancing. Standing this way turns off the lateral and posterior hip muscles that are built and positioned for supporting my full weight without undue stress on my joints. Try standing and putting your hands on the lateral and posterior hip with the hips pushed forward. You can easily feel that the muscles are not working to hold you up. This helps the mind to see objectively what you are doing and how it is affecting your ability to stand with stability. In other words, this recognition by the mind is essential for you to balance.

The word “balance” can also be used as a noun in which case the meaning will be quite different. “Balance” as a noun means not something I do but rather something I have. Taking the earlier example, if I simply say to you, “stand on one leg,” it suggests something very different than “balance on one leg”. If you stand on one leg, your effort will be directed toward standing rather than balancing. This will automatically lead to greater stability.

In the earlier example of standing with the hips pushed forward, the word “standing” is really the wrong word. Standing with the hips pushed forward is not really standing but rather falling forward and being held up by the quadraceps. Before you can have the quality of balance you must first stand. If your ability to stand, whether it be on one leg or two, is well developed then the whole notion of “balancing” is a non-issue. Your standing is stable and therefore you are stable. You have that quality.

In yoga we seek to move beyond balance as something we do or something we have and realize that is it something we are. We seek to reveal balance as simply one aspect of our nature. Discovering correct alignment of the body through recognition by the mind (such as seeing that we habitually “stand” with our hips pushed forward and then backing the hips up and actually standing with the hips aligned over the ankles) is an important part of this.

As a human being with a body and a mind, I am subject to the universal laws which govern life, including the laws of physics which govern my physical movements. In practicing yoga I am teaching the mind to recognize these laws and the body to express itself with respect to them. When this happens, I am doing yoga, and control, calm, equanimity and grace manifest automatically.

Are we walking or falling?

in BalanceWalking is one of the most basic human functions and one that we tend to take for granted. That is until we sprain an ankle or break a toe or god forbid break a leg and we’re either not able to walk or our ability to walk is hampered. In these circumstances we’d do almost anything to “walk normally” again.

Walking is essential to our health and longevity. A 2010 study of 428 hip fracture patients age 65 and older showed a 3 fold increase in mortality risk compared with the general population. And that included every major cause of death. It seems reasonable to surmise from these statistics that a sudden suspension in the ability to walk can lead to a rapid decrease in overall health and longevity. Clearly we don’t want to stop walking.

There are any number of studies and medical opinions that indicate that walking is perhaps the best form of exercise. Regular walking has been linked to a decrease in risk of several serious diseases including cardiovascular disease and Type 2 Diabetes. But are we really walking? This depends on how we define walking; and realizing an accurate definition of walking is greatly enhanced by some understanding of the biomechanics of human gait.

Most definitions of human walking are characterized by 2 things: a moderate or slow pace and never having both feet off the ground at once. In other words, not running or jumping. But what about falling? Do we need to completely fall down on the ground for it to be considered a fall? Might we simply be falling from one foot to the other at a moderate pace rather than actually walking? The fact is, most of us are ambulating by way of a somewhat controlled fall.

Figure 1

This is illustrated by understanding one very key feature of walking from the standpoint of biomechanics – walking should be posteriorly driven. This means we must push backward to move forward. For this to happen we need to have our center of gravity under our trunk and not out in front. Human movement where the center of gravity (about where our hip joints are) stays under the trunk is walking. Human movement where our center of gravity is pushed out in front of our trunk is falling.

Seeing the truth of this is easy. Stand up, push your hips forward (see figure 1) and then lift one foot off the floor without bending your knees. Notice how the lifted foot moved forward. In fact, you may have felt you needed this lifted foot to catch you from falling forward. This is the way most of us are ambulating – falling from one foot to the other.

Try the following instead. Stand and deliberately back your hips up such that your hip joints are aligned vertically over the outer ankle bones (see figure 2). Now lift one foot off the floor without bending your knees. What happened to the lifted foot this time? Chances are it didn’t go anywhere. That’s because you needed to push your standing leg thigh and hip backward in order to move your body forward. Try it again and see what happens if you lift the leg and then push your standing leg heel down and push your thigh back. Viola! That’s walking.

Figure 2

Actually, walking is much more complex that this. It involves a rather staggering number of muscles (600), joints (230) and bones (200). But it can be broken down into 2 basic motor skills. The first is what I described in the previous paragraph. That is, ‘posterior push off’. The second is called ‘pelvic list’.

If you tried the experiment above and succeeded, you’ve just done a pelvic list. A pelvic list is basically using the downward force of one straight leg to lift the other (see figure 3). This action recruits the lateral and posterior hip muscles which are a big source of stability for us when standing and walking. But this is only true when the hips are not pushed forward. If the hips are pushed forward then we’re not able to effectively recruit the lateral and posterior hip and we’re forced to use the quadriceps, forefoot and toes to hold us up. Not only will this lead to foot, knee and hip problems, this will also produce a gait pattern that is far from optimal.

Figure 3

If you tried the experiment above and found that you weren’t able lift one leg up with both knees straight, particularly when your hips were backed up, then you are currently unable to do a pelvic list. This means that whatever you might call how you ambulate, it isn’t really walking, not from a biomechanic standpoint. You’ll want to work on this regularly until it’s easy for you. Then you can actually start walking again and begin to get the many cardiovascular, strength and bone building benefits of what is arguably the most important and health promoting of human functions.

The importance of sending the right message

in BalanceAs a teacher of yoga and restorative exercise, a big part of my work is communication. To be effective, I must convey my instructions clearly to my students. To help my students achieve their goals, I must also teach them how to communicate with their own bodies.

The human body responds perfectly to the messages we send it. Our muscles, for example, being the means by which we move our bones, will always respond to the position we place our bones. One bone position will tell a particular muscle to contract while a different position of the same bone will tell the same muscle to relax. One relative position of two bones, such as the bones at the two ends of a particular muscle, will require that the muscle increase its length. A different position of the same two bones won’t require such an increase or may even require the muscle be shorter.

Understanding how our muscles respond to our bone placement will help us better understand how to effect muscles in the way we desire. If for example I want to strengthen a particular muscle, I need to position the bones that muscle attaches to in a way that loads that muscle against gravity. If I want to stretch a particular muscle or, increase it’s length, then I want to make sure that the bones at the two ends of that muscle are moved in opposite directions.

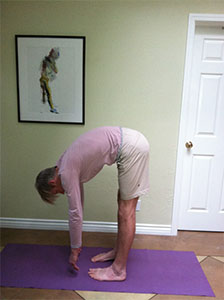

When standing upright, for example, the position of my thigh bone will have a big effect on the muscles that contract to support my upright posture. If I stand with my hips over my knees and ankles and therefore with the thigh bones completely vertical, my hamstrings and gluteal muscles will contract in order to help hold me upright (see the photo to the left). This alignment of my thighs and the corresponding support of the posterior muscles of my hips and legs helps to keep the “load” of my head, trunk and pelvis firmly on the bones of my legs. The loading of these bones against gravity minimizes the impact of the load on my knees, ankles and feet and helps to improve circulation and stimulate bone growth in my legs.

If however I stand with my hips and thigh bones forward of my knees and ankles, my quadraceps on the front of my thighs must contract to help prevent me from falling forward, I am sending my muscles a very different message. This alignment transfers the load from the back of my legs and hips to the front of my hips, knees, ankles and feet. In contrast to the “load profile” described in the previous paragraph, this “hips forward” alignment puts much more stress on these joints. This alignment also sends the message to the hamstrings and posterior hip muscles to relax, robbing the hips of a great deal of important muscular support and placing a further load on the hip joints (see the photo just below).

Another significant effect of placing my hips forward of my knees and ankles while standing is the resulting posterior tilt or “tuck” of the pelvis. When the pelvis tilts backwards this way, the sit bones, a primary attachment point of the hamstrings, are brought closer to the back of the knees at the other end of the hamstrings. When these two attachment points of the hamstrings are brought closer together, the message to the hamstrings is “get shorter”. This effect, provided very willingly by the hamstrings on my request, serves to anchor the pelvis in this backward tilt, placing a greater load when standing or bending forward on the spine and further exacerbating the undesirable effects described above.

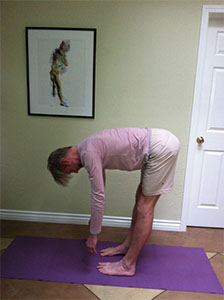

If I recognize this effect on my hamstrings, I may take the very correct and intelligent course of deciding to stretch the hamstrings to increase their length. A standing forward bend can be an effective way to increase the length of my hamstrings. And if I’m to successfully increase their length, I want to make sure the message I’m sending to the hamstrings is a clear message. It is therefore important that I start by bringing the hips back and allow the pelvis to tilt forward. I thus remove the conflicting message of allowing the pelvis to tuck and the hamstrings to maintain their shortened length. If I “un-tuck” the pelvis first my message to the hamstrings is very clear, “get longer!” But without this first step of backing the hips up and un-tucking the pelvis, the message I’m sending is either very different or at the very least diluted, and I won’t succeed in my efforts. This effect is highlighted in the two forward bends depicted in the photos below.

The above scenario is just one example of the many ways that seemingly small changes in the alignment of my bones dramatically changes the message I am sending to my muscles. It also highlights how the corresponding effects on my health and function can be just as dramatic. If I want to improve the health and function of the body, it’s not enough to just know the correct course of action. I also need to make sure I send the right message.

The Importance of Alignment

in Balance, Health Article, Movement Article, YogaI was first introduced to alignment in the context of yoga. The Iyengar Yoga system in particular is often characterized as emphasizing “alignment” in postures. It’s only recently, however, with the study of biomechanics, that I have begun to understand better what alignment really means and why it’s so important.

Katy Bowman, M.S., whose work I’ve been studying describes our alignment as being distinct from our posture. She points out that posture is cultural while alignment is based on objectivity. For example, some women I have talked to about posture and alignment have told me that their parents encouraged them not “to stick their butts out.” This view of posture is purely subjective as it is based a particular point of view. Alignment must be objective and must therefore be based solely on identifiable objective markers.

One such marker is the alignment of the hips relative to that of the knees and ankles. When standing in a bio-mechanically functional alignment the hip joints must sit directly over the center of the knees and the center of the outer ankle bones. Most of us tend to stand with the hips pushed forward of the knees and ankles. This tends to rotate the pelvis back (posteriorly) such that the pelvis sits a little “tucked”. To correct this misalignment we must back our hips up until our hip joints align over the outer ankle bones. When the hips are backed up this way it not only brings the pelvis and hips into a more functional alignment with the legs, it also tends to correct the “tuck” of the pelvis and rotate the pelvis back to neutral.

Figure 2

When I ask students to back their hips up this way, they usually say they feel like they are “sticking their butt out,” something some have been deliberately trying NOT to do! This is partly because they’ve gotten so accustomed to having their hips forward and their pelvis tucked that this misaligned position feels normal and the new position feels “strange” or “wrong” relative to what they are used to.

This example is a strong argument for using objective markers when aligning our bodies. We cannot rely on what “feels right” to us. When it comes to our own bodies we are not all that objective.

Besides the fact that it just feels right to push the hips forward, there’s another reason we tend to stand with our hips pushed forward – it’s easier! Standing with the hips forward is essentially us sitting loosely into the front of our hip joints. We often do the same thing to one side, swaying the hip out to act as a fulcrum to support our weight. This puts a great deal of stress on our hip joints and will eventually lead to pain. It takes a lot less effort to stand this way because the bones are in a position that doesn’t require (or to some extent even allow) important stabilizing muscles in our hips to work. When we back the hips up and align the hip joints with the outer ankles bones, it suddenly takes a lot more effort to stand!

This alignment of the hip joints helps a great deal in yoga with many of the standing postures. In the posture “samasthithahi,” for instance, where I am standing with my feet “hips width” apart (as opposed to “tadasana” where the feet are kept together), judging the position of the hips relative to the knees and ankles can be done by using a belt with a buckle as a plum bob to tell if my hips are lined vertically up over the outer ankle bones (see the diagram above). When I get the hips aligned I can feel that I’m anchored through the heels and the legs and hips are active and alive while I have a distinct sense of depth and space in the groin. Re-establishing neutral pelvis also does wonders for the function of the pelvic floor and is an essential step in the practice of the mula bandha.

Most importantly, aligning the hips properly in a yoga posture brings life into the posture. And this is not just true for samasthitahi but can be applied in many of the standing postures including trikonasana, parsvakonasana and ardhachandrasana to name just a few. In fact, this bringing of life into the postures can be manifested in just about any yoga posture when I can establish a better anchored and neutral pelvis.

Bio-mechanically sound alignment in yoga postures not only makes them better postures, it also helps us avoid injury and derive more benefit from our postures. So it’s worth the time and energy in a yoga practice to improve our alignment.

But ultimately, it’s our day to day activities that have the biggest impact on our health and function. Therefore alignment should not be limited to the domain of yoga but be a feature of how I stand, sit, walk and move throughout the day. In fact, the better my alignment in these every day activities the better my yoga postures will also become.

What I’m Teaching Now

in Balance, YogaAfter teaching yoga now for nearly 20 years my teaching has undergone quite a few changes, but there have been 2 major shifts. The first was when I stopped teaching Ashtanga Yoga (as taught be Pattabhi Jois, may he rest in peace) and started teaching in a way that most students have characterized as “Iyengar Yoga.” I have never received any formal certification in this system, but for about 13 years my teaching has drawn heavily on my studies with Ramanand Patel who holds a senior level teaching certificate in Iyengar Yoga and studied closely with B.K.S. Iyengar for many years.

The second major shift in my teaching started over a year ago and is continuing now. For more than a year I have been studying bio-mechanics and the work of Katy Bowman, MS. I have found that what Katy teaches, which incidentally I consider to be somewhat out of the realm of yoga, has a lot to say about how to practice yoga and how to teach it.

Those of you who take my classes have seen this shift happening. It has not been easy as it has forced me to reconsider nearly every instruction I give in every posture. It has, however, begun to transform my work in a profound way. This has been especially true when doing therapeutic work. I am seeing much better results working with the wide variety of health issues that clients present to me every day. I am also better able to help clients translate the work they do with me at Sadhana Therapies into better health and function in their daily lives.

Part of the challenge with this change is to begin to describe what I’m doing, perhaps name it. I’m not going to rush into this as the name is very important and will no doubt contribute to setting the tone for the future of our business. For now, I am just going to call what I”m teaching “yoga” and leave it at that. But here’s a bit more info on the kind of “yoga” I’m teaching now.

The yoga I am currently teaching focuses on “Yogasana” or the study and practice of yoga postures or “asana” for promoting optimal physical, mental and spiritual wellbeing. While any number of a vast array of classical yoga postures may be employed this way, it is the more basic, foundational postures that are the most essential for success.

Foundational postures tend to be the most similar to the postures we use in our daily life and can therefore have the greatest impact on health and function. Simply standing, walking and sitting in a well aligned, mindful way can have a huge impact on our health on a variety of different levels. When sound bio-mechanics and mindful awareness are applied to daily activities it can mean the difference between an activity that builds our strength, stability and flexibility and one that damages our joints, weakens our muscles and bones, degrades our function and shortens our lifespan.

Any activity that we take up for the purpose of our health must therefore be bio-mechanically sound. Bio-mechanically sound posture and movement must also have the effect of either reducing the impact of stress on our health or support our ability to better respond to and recover from it. This is especially true of yogasana. Yoga postures can be approached, modified and sequenced to enhance alignment and support function and therefore reduce and even reverse the effects of stress, both on and off the mat!

Of course, the impact of stress is not limited to the physical body. Very often the mental effects of stress are an even bigger issue. It is with respect to managing mental stress that yogasana really shines.

Above all else, yoga is a tool for training the mind. Yogasana is an important part of this as it begins to develop our mind’s ability to pay attention to and perceive the feedback it receives from our body through the senses. Yogasana also builds our capacity for discernment which helps us to act willfully and intelligently, rather than simply Re-acting. It is by way of this attentiveness that the mind can begin to see itself more clearly and through discernment that it begins respond in situationallly appropriate ways.

Discernment also enables the mind to see its patterns which is the first step toward changing those patterns. This leads to the kind of growth which we might call “spiritual.” Whether we want to cultivate this kind of growth, or not, is a question each of us must eventually answer at some point when doing yoga. This kind of growth requires a lot of honesty with ourself. And this may be a subject for a different post.

At the very least we should be honest with ourselves about why we are doing yoga. If health is the reason, alignment and bio-mechanics have a lot to offer any yoga student.

Recent Blog Posts

Newsletter

Contact Us

Alignment Lab

14 Dutton Court

Sausalito, CA 94965

415-599-5986 (Robert)

415-465-0131 (Tiffany)

Email: Robert Brook

Email: Tiffany Turley