A Deeper Look at Pelvic Floor Strength and How to Build It – Part 1

A quick online search for “strengthen the pelvic floor” reveals a lot about how many of us view the pelvic floor and its role in our health and function. There are any number of recommended exercises for the pelvic floor, some that include products to assist you, and with most advocating an approach that involves isolating the contraction of the pelvic floor muscles. This approach can be helpful for building some basic awareness of the pelvic floor – an important component of developing pelvic floor strength. But this approach is also limited in that it fails to address the broader and more essential role of the pelvic floor in facilitating alignment and functional movement.

The Pelvic Floor Does Not Work in Isolation

The pelvic floor muscles coordinate with several deep muscles in the trunk in order to stabilize the lower trunk and maintain the integrity of the pelvic organs, preserving continence and sexual function. These deep trunk muscles work synergistically with the pelvic floor and include the diaphragm, psoas, spinal muscles and the deep abdominal muscles. Collectively these muscles act as a flexible cylindrical, called the Thoraco-lumbar cylinder or TLC, with the pelvic floor forming the bottom of the cylinder. In addition to the muscles themselves we have a fascial layer that acts as a web-like connection between them. This facial layer interweaves the trunk and pelvic floor muscles and helps give the trunk and pelvis its shape and tone.

Diaphragmatic Breathing is Essential for Pelvic Floor Strength

This fascial connection between the trunk muscles and the pelvic floor assures no individual muscle will work properly unless there is appropriate movement and engagement in all of the muscles that form the cylinder. In other words, the pelvic floor muscles never contract in isolation, rather they co-contract in response to the movement of the diaphragm and the subsequent abdominal response needed to support the trunk. This means that in order to strengthen the pelvic floor we must breath diaphragmatically, and to maintain consistent optimal pelvic floor tone we must breath diaphragmatically throughout the day and especially during any exercise or activity.

The Role of Intra-abdominal Pressure

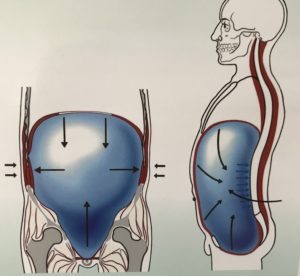

When we breath diaphragmatically, pressure is created inside the TLC which is similar to the pressure created inside a ballon filling with air. This pressure is called intra-abdominal pressure (IAP), and under ideal circumstances the muscles forming the TLC all respond to this pressure by contracting against it. This response should be relatively equal throughout the walls of the cylinder and serves to contain, maintain and regulate the IAP. Maintaining IAP helps us avoid stress on the pelvic and abdominal organs, spinal muscles and vertebral joints. Thus the pelvic floor has the important role of regulating IAP by helping to maintain relatively constant control of the cylinder, and in this way the relative tone of the pelvic floor directly influences the strength and function of the whole lower trunk.

If we do not breath diaphragmatically then we do not create proper IAP, and without proper IAP there simply cannot be the coordinated contraction of all the muscles of the cylinder necessary for trunk stability. In other words, there will be no response in the pelvic floor muscles if we are not breathing correctly.

Picture this: upon inhalation the pelvic floor widens to support the downward pressure created by the diaphragm. Then upon exhalation the pelvic floor co-contracts with the diaphragm and moves slightly up into the pelvis while the diaphragm moves back up into the ribcage. This coordinated movement between diaphragm and pelvic floor has a gentle squeezing effect on the spinal column and disks, keeping them plumb and lengthening the spine. This protects the joints of the spine from wear and tear and prevents damage to the disks.

Before beginning any pelvic floor specific strengthening exercises, diaphragmatic breathing with correct intra-abdominal pressure must be mastered!

For some people diaphragmatic breathing may be challenging at first, particularly if there is a a lot of tension in the trunk muscles. For others, years of chest breathing and/or shallow breathing can also make the trunk muscles weak and the back muscles too tight, preventing the alignment of the pelvis and ribcage necessary for diaphragmatic breathing to occur. Very often in these circumstances the pelvic floor muscles themselves are too tight, and this tension increases the tendency for pelvic floor disfunction.

Signs of and Contributors to Pelvic Floor Tension

Signs of a tight pelvic floor include lower back pain, incontinence issues, prostate and or bladder issues, prolapsed organs, and impairment of sexual function. Typically a tight pelvic floor is accompanied by certain muscular habits that manifest in conjunction with the pelvic floor tension. Habits that contribute to pelvic floor tension include clenching the lower glutes, tucking the pelvis, and sucking in the abdominal wall.

We live in a busy, stressful world and all of us are subject to potential stressors daily. An overactive stress response, either accompanying or even caused by long term habitual chest breathing is another important cause to be considered with pelvic floor disfunction (PFD). In such cases an effective approach to stress reduction is an essential component to any remedy.

Many of us have jobs that require a lot of sitting, either at the office and/or in the car on the way and home again. Those of us in this group are especially at risk of developing pelvic floor disfunction because long term sitting increases pelvic floor tension. The employment of a standing desk can help in these instances, but a more careful look at how we’re standing, or sitting, is an important part of any long term resolution.

Ignoring calls of nature because of busyness or distraction can be yet another source of stress that directly contributes to pelvic floor tightness and disfunction in a very obvious way. “Holding it” can become a habit that should be taken seriously, especially if PFD has already manifested.

Less obvious but no less important a contributor to PFD are cultural influences and images that present alignment pattens that we may try to emulate. Patterns such as a military posture with its arched lower back and tight glutes, as well as images from the fashion industry presenting beauty in the form of female bodies with forward hips and tucked pelvises no doubt reinforce patterns in younger people who are already developing these patterns through excessive sitting and staring at screens. Limiting screen time and setting healthier examples with our own alignment and movement habits are important considerations when managing this issue with our children.

Even in the wellness/fitness industry we are regularly presented with images of “healthy” bodies with sucked in over developed abdominals that are bulging and tight. We must remember that muscles that are too tight are also too weak to be functional. In order for a muscle to function well, it must have its full range of motion and be able to both contract well AND relax well. This is important to keep in mind not only with respect to aesthetics, but also with respect to steps we might take to mange pain. Bracing with the abs to manage back pain or PFD, for instance, is one of many habits that may be contributing to rather than solving our PFD.

A psoas release is a simple yet extremely effective way to help to begin to release many of the habits that contribute to PFD:

Once you begin to breath diaphragmatically and freely throughout the day and you combine it with a daily practice of letting go of dysfunctional tension habits, you will be ready to practice more specific pelvic floor re-training and strengthening. Because of the inter-connected fascial webbing, strengthening your pelvic floor muscle necessitates the ability to feel and develop responsiveness to the co-contraction of the muscles of the thoracolumbar cylinder.

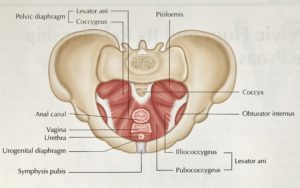

Since the pelvic floor muscles are hard to feel, it can help to have a basic understanding of their anatomy to visualize and increase awareness of them. The pelvic floor muscles connect the pubic bone to the tailbone and each ischial tuberosity (sitting bone) to the other, and these muscles reside in three detailed layers.

Again, pelvic floor muscles are part of a deep myofascial grouping (close to bones and deep in the body), and because they are deep within the body these muscles are hard to sense. The function of these deeper muscles can also appear more subtle than that of the large superficial muscles like the quadriceps or gluteals which are much easier to feel and to activate.

But the deeper muscles of the trunk contain a larger amount of proprioceptive nerves than the superficial muscles, and these nerves help our body respond to changes in movement and loads quicker than our superficial muscles can – even quicker than we can respond with our thoughts. This is why symptoms of mild incontinence often occur with quick motions like jumping, running, and sneezing. Each of these motions requires the deeper muscles to be strong and responsive in order to manage the increased loads these and other movements may place on the pelvis and lower trunk. Strong and responsive trunk and pelvic floor muscles serve to prevent excessive loading of the bladder and urethra which might otherwise cause leaking.

To help you feel how these muscles co-contract together, here is a simple exercise:

In part 2 of this post we will look further at how to further strengthen the pelvic floor with more dynamic movements that involve bending, lifting and walking. Stay tuned!