Adaptation and the Psoas

When we’re faced with pain it’s easy to wonder, “why did this happen to me?” Seeking a cause for pain can be helpful, but only if we’re willing to consider the possibility that the pain is the result of how we’ve been using our body, or in many cases, not using it.

Human beings as a species have been successful on this planet largely due to our uncanny ability to adapt to our environment. Our bodies are extremely well adapted to the hunter gatherer lifestyle of our distant ancestors, for example, and like these ancestors we thrive on a wide variety of foods and the great number of human movements once required to collect them.

The breakneck pace of technology, however, has placed great demands on our ability to adapt to changes in diet and lifestyle. With very high calorie foods so easy to come by with so little physical effort, even relatively young people must all guard against diseases unheard of in the few hunter gatherer populations still remaining on this planet.

Perhaps the solution is getting more exercise, but this is highly debatable. The true purpose of exercise is to provide a substitute for the movement we’re not doing and the calories we’re not using in our increasingly technologically driven and sedentary modern lifestyle, but most of what we do for exercise these days reinforces the very lifestyle habits we’re already spending most of our days doing. Is sitting on a bike pedaling for an hour better than siting still in a chair? Maybe a bit, but it’s still sitting and can still contribute to many of the same health consequences.

In her 2015 book Don’t Just Sit There, Katy Bowman speaks to this issue when she says “the sitting itself isn’t really the problem, it is the repetitive use of a single position than makes us literally become ill in a litany of ways.” She goes on to give several examples including that “muscles will adapt to repetitive positioning by changing their cellular makeup, which in turn leads to less joint range of motion.”

I find myself telling my clients and students constantly that muscles adapt to the position we put our bones in. For instance If I stand with my hip joints forward of my knees and ankles, my hamstrings and calve muscles will shorten, limiting my ability to bend forward from my hips and placing greater demands on muscles and joints in my lower back.

These “adaptive” changes manifest to a certain extent over a period of time, but in some cases this type of adaptation can be very quick, even instantaneous. In the hips forward misalignment described above, the affects on muscle length and range of motion can actually happen rather quickly. Standing with the hips pushed forward turns off the muscles in the posterior hip and lower back. This doesn’t take any time at all, it simply happens as a result of doing it.

This turning off of the hip muscles is also a kind of adaptation and I actually consider this good news for us modern humans. It demonstrates that our bodies have the ability to make some changes rather quickly and that these changes can just as easily be good for our health and function as bad.

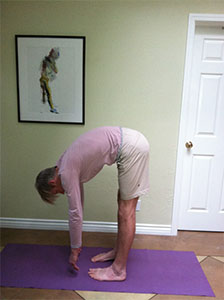

My favorite example of soliciting a positive change in the body that can have huge benefits to our health and function is what happens in the Psoas Release. I use this posture as much as any I teach my students and clients because I’ve seen how effective it can be in retuning the psoas muscles to a more functional length. This is important as psoas that are too short have a huge impact on our health and function in a variety of ways.

The psoas muscles are rather large muscles that attaches to the inner, upper femur at one end and to a number of locations along the lumbar spine at the other. The psoas run through the pelvis but do not attach directly to it. The psoas do however have a big impact on the alignment of the pelvis as well as the alignment of the lumbar spine. One impact they can have on the pelvis is the very misalignment pattern described above – causing the hips (and the pelvis along with them) to sit forward of the knees and ankles and therefore shortened psoas can directly contribute to limited hip strength and limited hip range of motion.

Other possible effects of short psoas muscles are numerous. Here are a few more:

- Compression of the lumbar discs

- Excessive load on the sacroilliac joints

- Increased risk of sciatica

- Restriction of the diaphragm and disruption of healthy respiratory function

- Inhibition of the pelvic floor tone

- Increased risk of high blood pressure

- Decreased circulation through the abdominal aorta

- Impairment of the digestive system

- Impairment of the urinary system

- Impairment of the reproductive system

- Ongoing activation of the sympathetic nervous system

Clearly there are a number of compelling reasons for have a longer, more functional psoas. So let’s look at the Psoas Release and learn a rather simple, gentle and effective way of bringing the psoas back to a more functional length. And did I mention that this pose can be very relaxing?